Dear Readers,

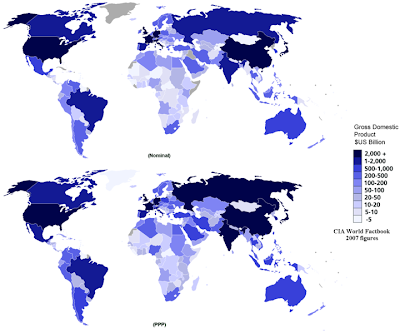

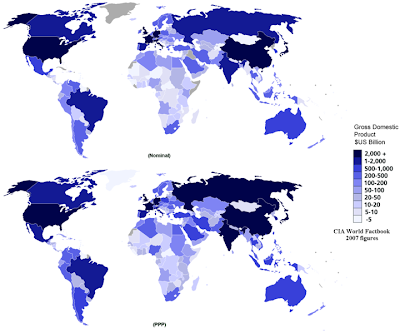

The world economy grew 5.2% in 2007 powered by growth in China (11%), India (9%) and Russia (8%). The global economy faces a real risk of 1970s style stagflation however, with resource constraints tighter than ever before. Things could scarcely have looked rosier for the world economy at the start of 2007. The Emerging Markets, led by the giants of China, India, Russia and Brazil (the BRIC countries) had been posting 7%-10% grow rates for years. Property and stock market booms had brought consistent growth in North America and Europe. Investment was bringing economic development to much of the Middle East and Africa, and even Japan was recovering from its deflationary ‘Lost Years’.Economic conditions within these countries play a major role in setting the economic atmosphere of less well-to-do nations and their economies. In many aspects, developing and less developed economies depend on the developed countries for their economic wellbeing. Theories were even circulating that thanks to the growth of the developing world, we might enjoy years of unfettered growth, as new markets would go through successive growth spurts and counter the effects of slowing growth elsewhere. It was suggested that Asia was ‘decoupling’ from the US and able to grow under its own steam thanks to its two ‘Awakening Giants’. What a difference a year makes. The global economy has been hit by a rapid one-two punch that may be setting the stage for stagflation to make a come-back. It started with the sub-prime crisis in the US, caused by loans to risky or ‘sub-prime’ mortgagees who did not have strong credit histories. While house prices were rising there wasn’t a problem. But as house prices slowed and then crashed to earth, default rates started to rise. To add fuel to the fire, sub-prime loans had been packaged and re-packaged in a range of derivative financial instruments such as Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs). It was not always clear what the contents CDOs consisted of, as they were combined, sliced and re-sold between financial institutions and funds, and which in some cases allowed risky debt such as sub-prime loans to be packaged as part of low-risk instruments. Vast swathes of CDO investments had to be written off, and banks became suspicious of investment, borrowing and lending, since it was not always clear what the underlying security was. Once banks stopped lending the Credit Crunch hit. We then witnessed extraordinary scenes of government regulators in US and UK having to help save collapsing banks in order to avert a meltdown of the financial system, and to Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) from the developing world taking large stakes in venerable western banks like Citibank and UBS in return for keeping them liquid. With house prices having fallen more than 20% in many areas of the United States, even prime mortgage holders now find themselves with negative equity. The federal government has been forced to step in and assume responsibility for both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, who between them back over half of all American mortgages. The second part of the one-two punch has involved the rise of commodity prices. Just before the dawn of the 21st century, oil average $16 a barrel. By July 2008, less than 10 years later, oil hit a high of $146 a barrel – a stunning rise of more than 800%. From early 2007 to mid 2008 alone the price has risen more than threefold from the mid $40s. During the Oil Crisis of the 1970s, oil spiked at a nominal peak of $38. In today’s prices (adjusted for inflation), that is $106, a figure that we blew past in early 2008. The price of food has also started spiraling. Rice and other grain prices have doubled from 2007 - 2008, leading to food riots in a score of developing markets. Most agricultural and farm produce prices have been going through the roof. In fact almost all commodities, including those used for energy, construction and consumption, have been rising rapidly. Price rises have been fueled by the demands of the emerging markets, particularly the BRIC nations, who together account for nearly 3 billion people. In order to maintain their high rates of growth and help lift more of their populace out of poverty, they require more and more commodities. A bigger worry for economists, however, is whether the natural resources exist to meet these burgeoning demands. A similar crisis was faced in the 1970s. After a period of strong global economic growth, when the world economy was averaging 5% a year GDP increases, the world hit supply constraints in oil and food. For the next fifteen years, global GDP growth slowed to an average of 3.2% per year. This became known as the stagflation era. Growth opportunities were limited, but prices continued to rise with a continued lack of supply. A great debate ensued as to whether we had reached the limits of the earth’s ability to support our growth. In 1972 the Club of Rome famously argued exactly that, saying that the global economy would collapse. And yet the opposite happened. According to Jeffrey D. Sachs, Director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University, world crude oil production grew from 21 million barrels per day in 1960 to 56 mbd in 1973, a growth of 166%. The stagflation crisis also brought about a ‘Green Revolution’ through fertilizer and irrigation development, and through the development of stronger seed strains. This led to much higher agricultural productivity levels. Since 1970 however, crude oil production has only grown 30% worldwide. More worrying still is that crude oil production in the Middle East has peaked at 21 mbd in 1974 and remained stagnant, while mature fields in the North Sea, Norway and Alaska are all in decline. In fact there is a growing school of thought known as ‘Peak Oil’ that believes we have – or will soon – reach peak oil production capabilities. In the 1950s Dr M. King Hubbert correctly predicted peak oil and decline rates for the mainland US oil industry. His model came to be known as The Hubbert Peak Theory. It predicts that world peak oil production will be reached sometime between 2000 and 2010, and will decline thereafter. This impending crisis has also helped to raise the price of food, since increasing amounts of land are being devoted to biodiesel crop development, and since higher oil prices raise the cost of fertilizer (for which petroleum is a key ingredient) and food transportation. It seems increasingly likely that a massive investment in renewable energy sources will be needed in order to avert another stagflationary period in the world economy, or even a global recession. The jury is still out as to how quickly oil supplies will decline or how fast alternative energy sources can be brought online. World Economic Statistics at a Glance

World GDP (PPP): $65 trillion

GDP Growth Rate: 5.2%

Growth Rate of Industrial Production: 5%

GDP By Sector: Services- 64%

Industry- 32%

Agriculture- 4%

GDP Per Capita (PPP): $9,774

Population: 6.65 billion

The Poor (Income below $2 per day): 3.25 billion (approximately 50%)Millionaires: 9 million (approximately 0.15%)

Labor Force: 3.13 billion

Exports: $13.87 trillion

Imports: $13.81 trillion

Inflation Rate – Developed Countries: 1% - 4%

Inflation Rate – Developing Countries: 5% - 20%

Unemployment – Developed Countries: 4% - 12%

Unemployment & Underemployment - Developing Countries: 20% - 40%